Sportsman as Writer

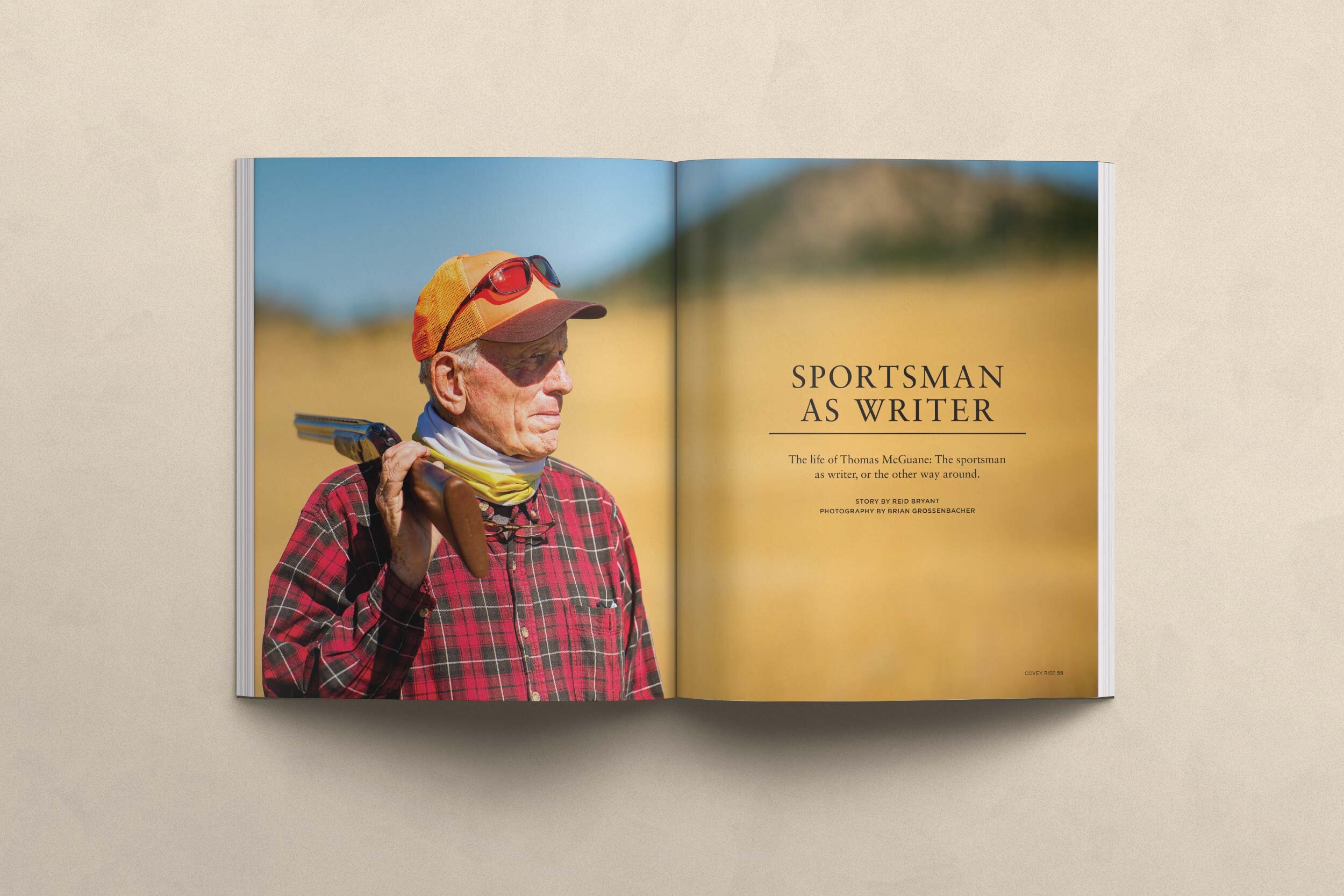

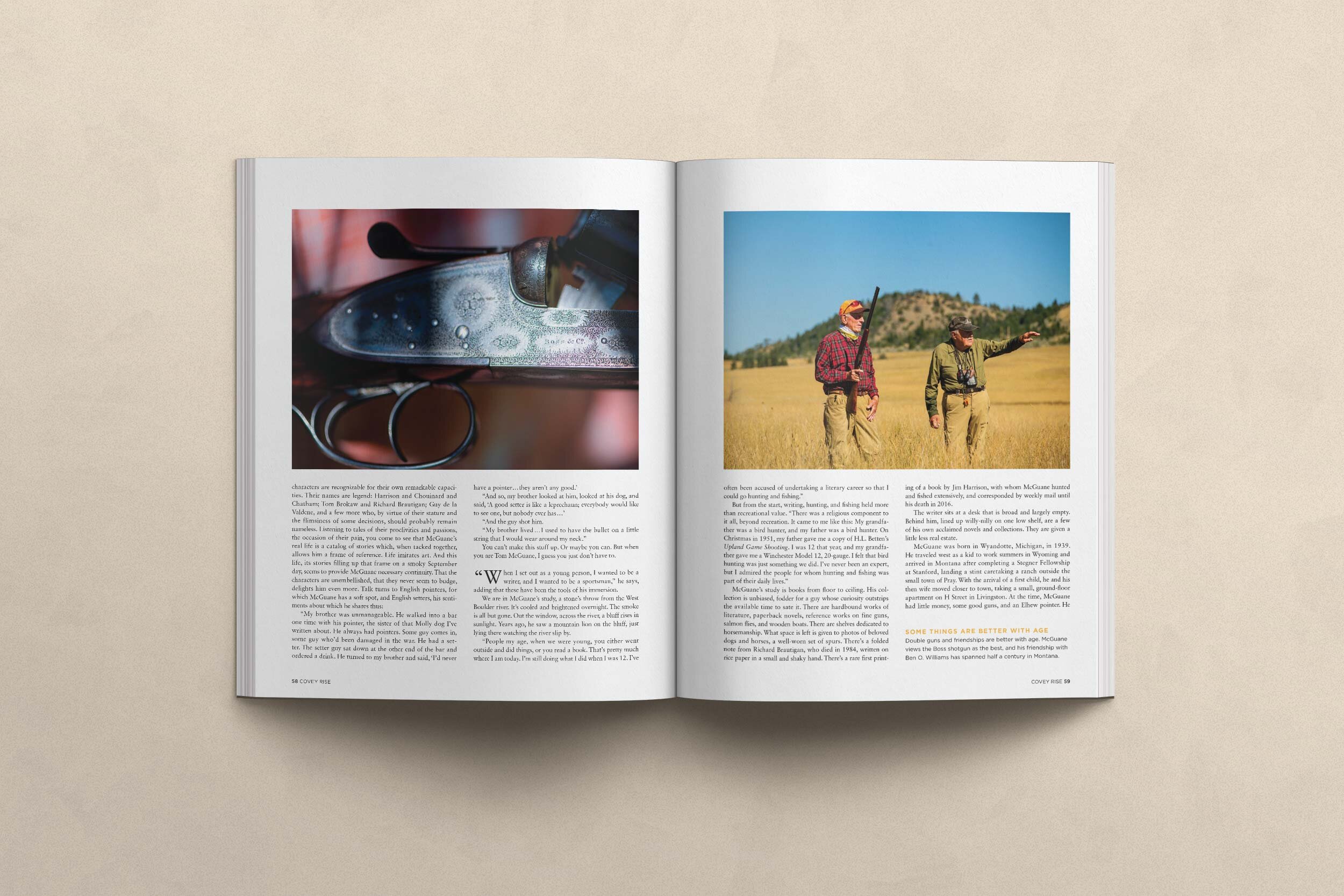

Thomas McGuane leans against the bed of a Toyota pickup with an orange in his hand. A tired Belgian Browning is propped against a tire. The top lever on the gun is well left of center, and the action is worn to white. I’d imagine that gun has been carried through some fine country; I’d imagine it’s been pointed at some birds.

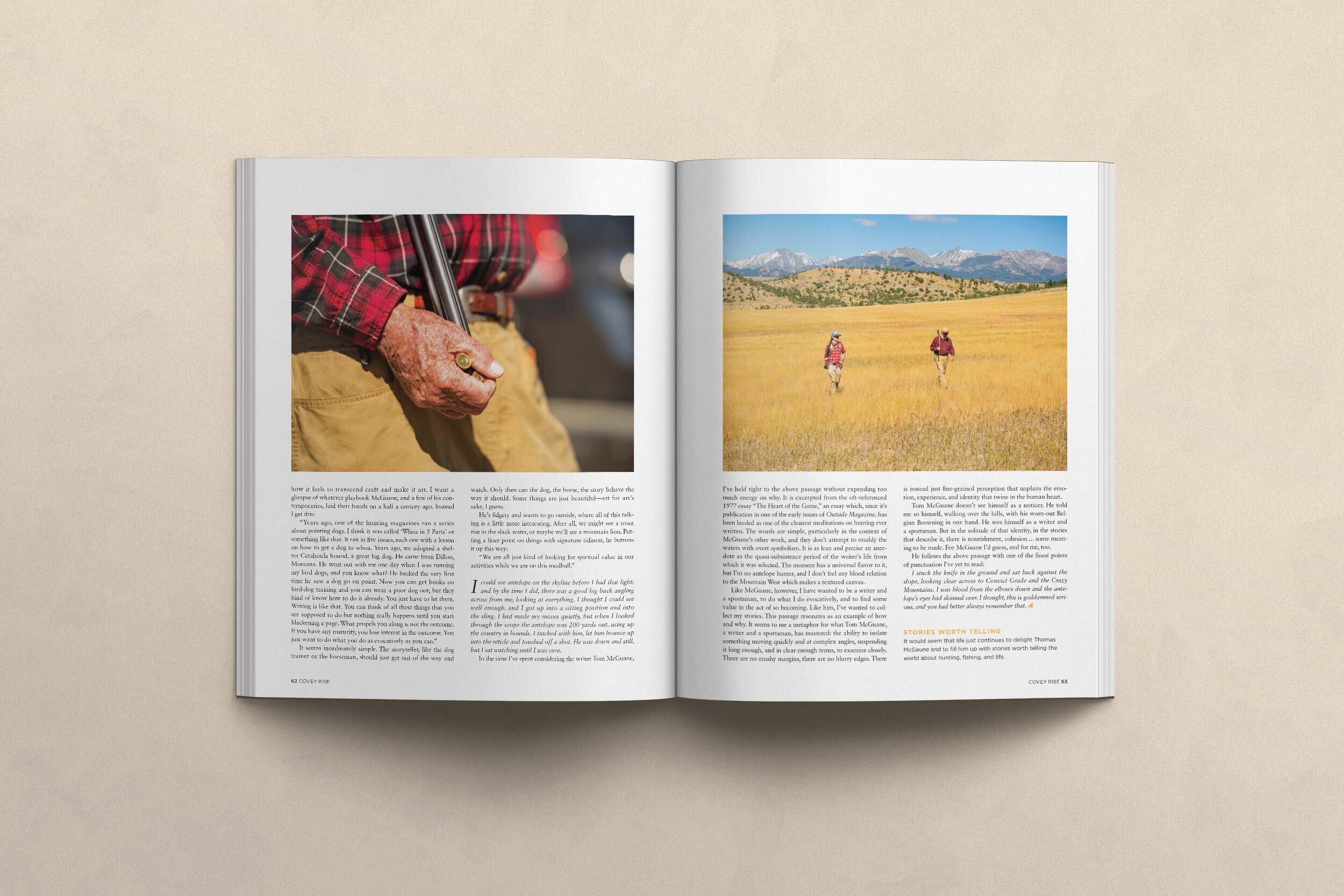

It’s September outside Livingston, Montana, and for the season far too dry. The fires above Bozeman have found the city margins and scorched some homes to ash. There is smoke in the air, and breathing is less profitable than it should be. The higher peaks of the Crazies are indistinct. It’s lunchtime. We’ve spent the morning wandering the grasslands and coulees, following a pair of Ben O. Williams’ pointers, who share our interest in partridge. We haven’t killed a bird… haven’t seen a Hun in fact, just a small covey of grouse that got up wild not far from the truck and piled over a piece of rimrock, clucking. We watched them set their wings and glide. We didn’t fire a shot.

Tom McGuane begins to peel his orange. I’m looking at his hands. They are scarred and steady from some eighty years of service. It is that service which has me thinking. From my perspective, Tom McGuane can make his hands do outstanding things. He can make them do things that are alien to me, like handle the reins of a cutting horse, or rope a steer, or pole a flats skiff into a quartering wind. He can make them do things that I know a little better, like land a dry fly whisper-quiet on a piece of moving river. They are the hands of a rancher and the hands of a writer, capable of requisite strength and delicacy. They are tools that conjure stories from dim places and out into the light.

Over a literary career that spans more than a half-century, McGuane has interpreted life for its honesty and its nuance, peeling back the skin of it, separating its whole into segments. He gathers in his hands the confluence of people, place, and emotion in the way a child gathers fireflies, watching closely as they shed their flame. In small moments, he tells entire stories. That some of those stories are made up of birds and dogs and sage-covered country makes them familiar; that they are given an artist’s attention makes them lovely.

I’m thinking about the things that hands can do, and McGuane is eating his orange. He’s been swapping stories with his old pal Ben for nearly an hour. Dogs scuffle in their boxes. McGuane is at home here, swapping stories, his back against a truck bed. It is a pleasure to hear him at his craft. The stories are set in and around Livingston, beside cold rivers and up winding canyon roads. The referenced characters are recognizable for their own remarkable capacities. Their names are legend: Harrison and Chouinard and Chatham; Tom Brokaw and Richard Brautigan; Guy de la Valdene… a few more who, by virtue of their stature, and the flimsiness some decisions, should probably remain nameless. Listening to tales of their proclivities and passions, the occasion of their pain, you come to see that McGuane’s real life is a catalog of stories which, when tacked together, allows him a frame of reference. Life imitates art. And this life, its stories filling up that frame on a smoky September day, seems to provide McGuane necessary continuity. That the characters are unembellished, that they never seem to budge, delights him even more. Talk turns to English pointers, for which McGuane has a soft spot, and English setters, his sentiments about which he shares thus:

“My brother was unmanageable. He walked into a bar one time with his pointer, the sister of that Molly dog I’ve written about. He always had pointers. Some guy comes in, some guy who’d been damaged in the war. He had a setter. The setter guy sat down at the other end of the bar and ordered a drink. He turned to my brother and said, ‘I’d never have a pointer… they aren’t any good.’

And so, my brother looked at him, looked at his dog, and said, “a good setter is like a Leprechaun; everybody would like to see one, but nobody ever has…’

And the guy shot him.

My brother lived… I used to have the bullet on a little string that I would wear around my neck.”

You can’t make this stuff up. Or maybe you can. But when you are Thomas McGuane, I guess you just don’t have to.

*

“When I set out as a young person, I wanted to be a writer, and I wanted to be a sportsman,” he says, adding that these have been the tools of his immersion.

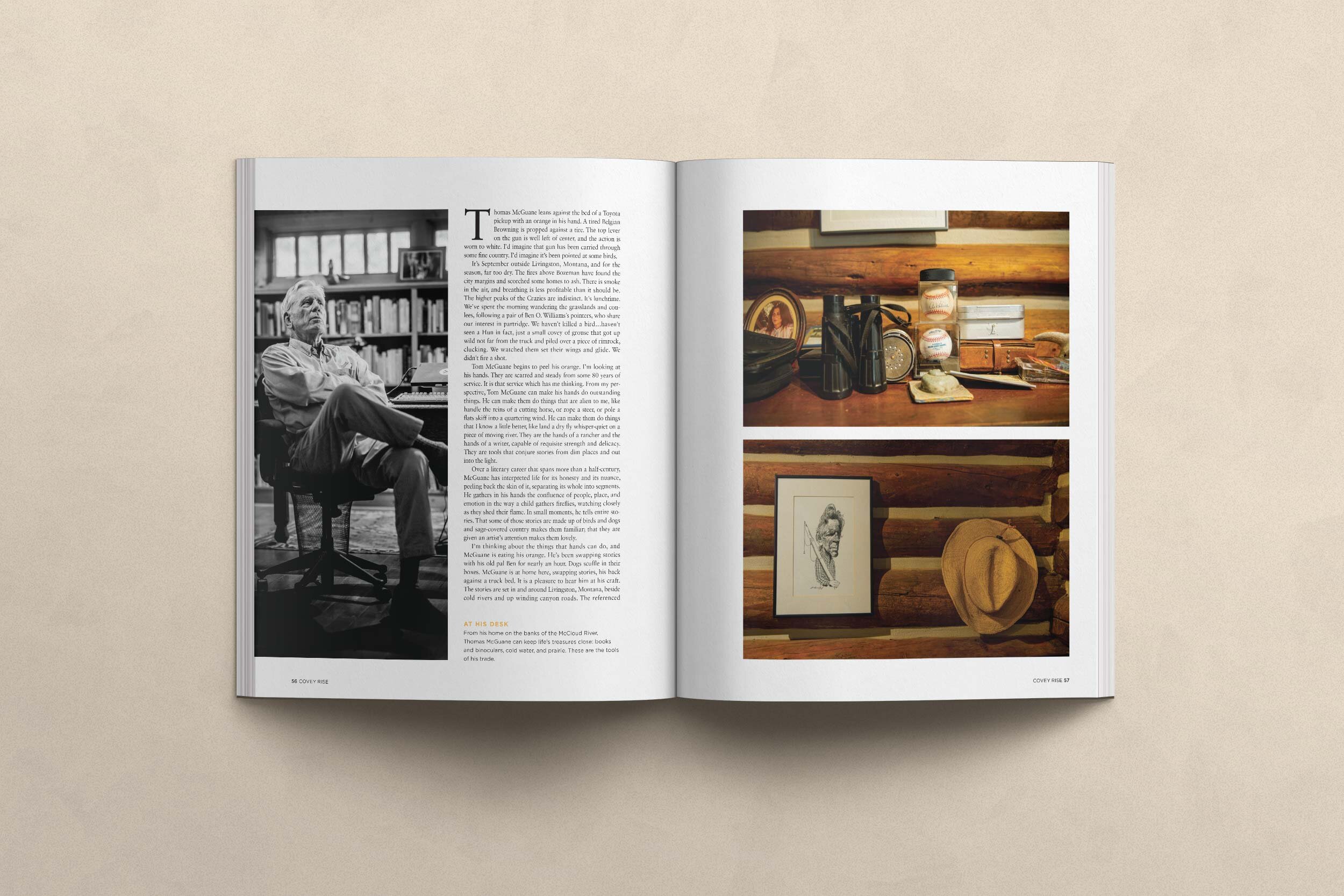

We are in McGuane’s study, a stone’s throw from the West Boulder river. It’s cooled and brightened overnight. The smoke is all but gone. Out the window, across the river, a bluff rises in sunlight. Years ago, he saw a mountain lion on the bluff, just lying there watching the river slip by.

“People my age, when we were young, you either went outside and did things, or you read a book. That’s pretty much where I am today; I’m still doing what I did when I was twelve. I’ve often been accused of undertaking a literary career so that I could go hunting and fishing.”

But from the start, writing, hunting, and fishing held more than recreational value. “There was a religious component to it all, beyond recreation. It came to me like this… My grandfather was a bird hunter, my father was a bird hunter. On Christmas in 1951 my father gave me a copy of H.L. Betten’s Upland Game Shooting. I was twelve that year, and my grandfather gave me a Winchester Model 12 twenty gauge. I felt that bird hunting was just something we did. I’ve never been an expert, but I admired the people for whom hunting and fishing was part of their daily lives.”

McGuane’s study is books from floor to ceiling. His collection is unbiased, fodder for a guy whose curiosity outstrips the available time to sate it. There are hardbound works of literature, paperback novels, reference works on fine guns, salmon flies, and wooden boats. There are shelves dedicated to horsemanship. What space is left is given to photos of beloved dogs and horses, a well-worn set of spurs. There’s a folded note from Richard Brautigan, who died in ’84, written on rice paper in a small and shaky hand; there’s a rare first printing of a book by Jim Harrison, with whom McGuane hunted and fished extensively, and corresponded by weekly mail until his death in 2016.

The writer sits at a desk that is broad and largely empty. Behind him, lined up willy-nilly on one low shelf, are a few of his own acclaimed novels and collections. They are given a little less real estate.

McGuane was born in Wyandotte, Michigan in 1939. He traveled west as a kid to work summers in Wyoming and arrived in Montana after completing a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford, landing a stint caretaking a ranch outside the small town of Pray. With the arrival of a first child, he and his then wife moved closer to town, taking a small, ground-floor apartment on H Street in Livingston. At the time, McGuane had little money, some good guns, and an Elhew pointer. He had a few ideas for stories, and a manuscript for 1969’s The Sporting Club under consideration. Writing was the calling, but he claims that at the time he had no clear sense of how he’d make a living. “The whole world of art and literature was like a priesthood. You have to remember - Hemingway and Faulkner were still writing when we started out. But the young writers that I knew were really driven, mostly because we’d burned all our bridges or had made this big bet. It’s much easier to make the New York Yankees than have a career as a novelist. And if you somehow forgot how the odds were against you, your mother and father would remind you.”

But Montana was fertile ground, what for its rugged beauty, its birds and brush-worn characters. And it welcomed him. He tells the story of his son’s first birthday, how the neighbors all showed up at his apartment with a birthday cake, one candle in the middle. They brought the little boy a baby rabbit. McGuane and his wife had not realized anyone even knew. “I just thought, ‘these are people I’d like to live around’”. Despite a few meanderings, he’s really never left.

“When I moved to Montana in the late 60’s things were not at all polarized. We weren’t hippies. We had long hair, but we were very hardworking. The us and them deal hadn’t set in at all. The cultural continuity was very complete.”

And so McGuane made his big bet, assuming at the very least that he’d have a sense of place. He wrote when he wasn’t outside. He hunted, and he fished. He became fascinated by horses and by rodeo, and he realized success in those disciplines too. He told his stories and he noticed things, lost himself in the details. His reputation as one of the finest young authors of a generation blossomed. He modeled characters and settings on the folks he knew the environments they frequented – frontier bars and small-town rodeo grounds and lonesome prairie dooryards, the suburbs of his Michigan youth, the Key West marinas out of which he fished. He and a growing cast of fellow artists and literary types migrated along similar routes. They converged around Livingston for a shared interest in birds, dogs, and trout, and the hardscrabble places they tend to live. Together, they watched life happening from oblique angles, and commented in their muse.

“There was a real vivid sporting scene around Livingston back then. Mostly it was storytelling, and very ceremonial.”

And so it goes. In the last fifty years Tom McGuane has captured what he’s noticed, watched it burn like a July firefly, turned it loose on us with whimsy and with elegance. He has created a body of work: ten novels, six nonfiction essay collections, two short-story collections, and several Hollywood screenplays. He is a regular contributor to The New Yorker, and a member of The American Academy of Arts and Letters, The National Cutting Horse Association Members Hall of Fame, and the Fly Fishing Hall of Fame. He still hunts and fishes in the same good country, no less delighted by what is right outside his door. The strung-up fly rod on the wall and the Elhew pointer in the yard are evidence of that. He is, I suppose, doing what made him happy when he was twelve.

I wonder how he sees himself, how eighty years of place and craft and unapologetic characters can color a man’s identity.

So, I ask.

“I’m just a writer,” he responds. “And that’s what I am. A writer, with a family and friends. That is the way I understand the other things I do.”

Nice compact answer.

But he’s a giant. I want something more. I want to know how it feels to transcend craft and make it art. I want a glimpse of whatever playbook McGuane, and a few of his contemporaries, laid their hands on a half a century ago. Instead I get this:

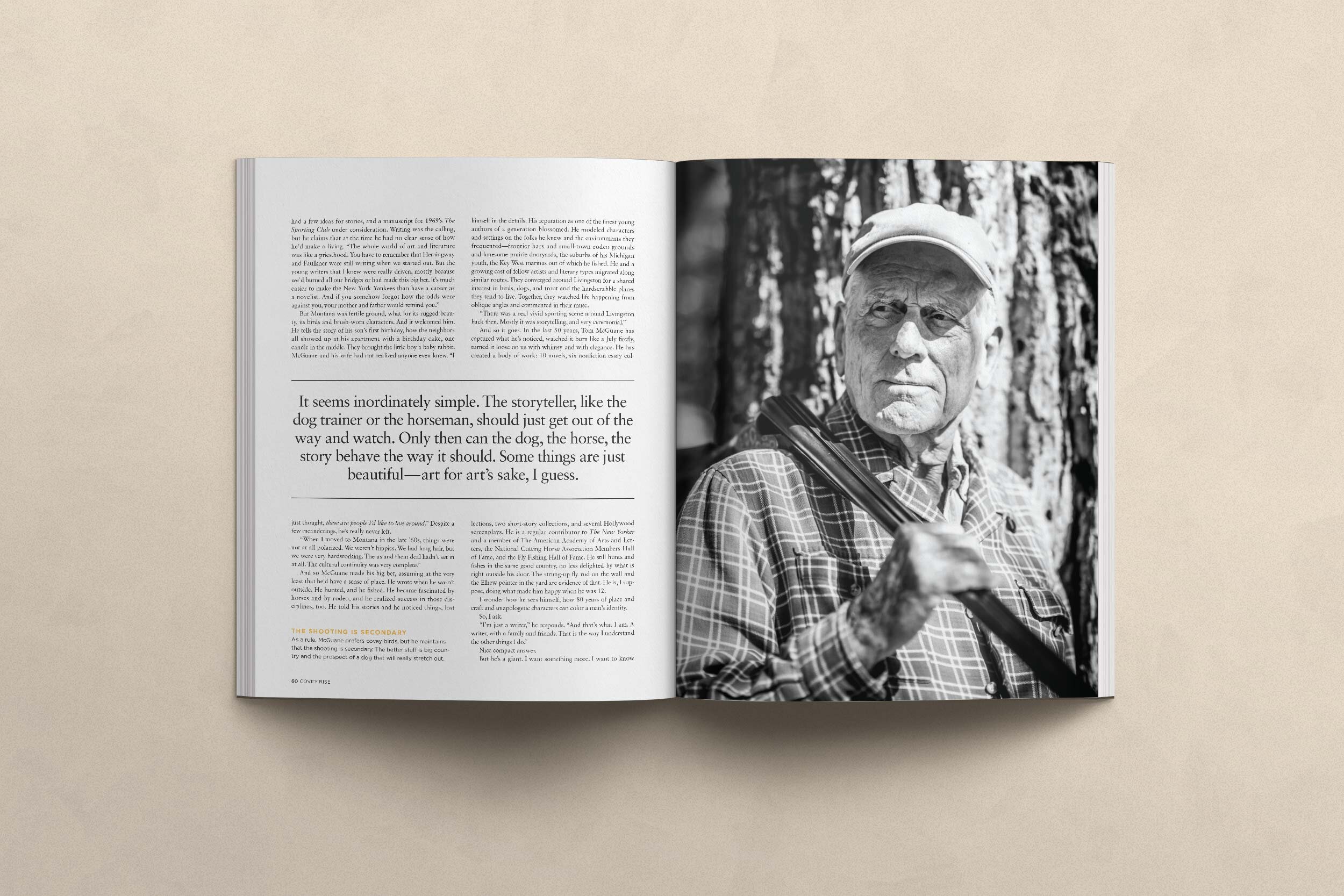

“Years ago, one of the hunting magazines ran a series about pointing dogs. I think it was called ‘Whoa in 5 Parts’ or something like that. It ran in 5 issues, each one with a lesson on how to get a dog to whoa. Years ago, we adopted a shelter Catahoula hound, a great big dog. He came from Dillon, Montana. He went out with me one day when I was running my bird dogs, and you know what? He backed the very first time he saw a dog go on point. Now you can get books on bird-dog training and you can wear a poor dog out, but they kind of know how to do it already. You just have to let them. Writing is like that. You can think of all these things that you are supposed to do but nothing really happens until you start blackening a page. What propels you along is not the outcome. If you have any maturity, you lose interest in the outcome. You just want to do what you do as evocatively as you can.”

It seems inordinately simple. The storyteller, like the dog trainer or the horseman, should just get out of the way and watch. Only then can the dog, the horse, the story, behave the way it should. Some things are just beautiful. Art for art’s sake, I guess.

He’s fidgety, and wants to go outside, where all of this talking is a little more interesting. After all, we might see a trout rise in the slack water, or maybe we’ll see a mountain lion. Putting a finer point on things with signature tidiness, he buttons it up this way:

“We are all just kind of looking for spiritual value in our activities while we are on this mudball.”

*

“I could see antelope on the skyline before I had that light; and by the time I did, there was a good big buck angling across from me, looking at everything. I thought I could see well enough, and I got up into a sitting position and into the sling. I had made my moves quietly, but when I looked through the scope the antelope was 200 yards out, using up the country in bounds. I tracked with him, let him bounce up into the reticle and touched off a shot. He was down and still, but I sat watching until I was sure.”

In the time I’ve spent considering the writer Thomas McGuane, I’ve held tight to the above passage without expending too much energy on why. It is excerpted from the oft-referenced 1977 essay “The Heart of the Game”, an essay which, since it’s publication in one of the early issues of Outside Magazine, has been lauded as one of the cleanest meditations on hunting ever written. The words are simple, particularly in the context of McGuane’s other work, and they don’t attempt to muddy the waters with overt symbolism; it is as lean and precise an anecdote as the quasi-subsistence period of the writer’s life from which it was selected. The moment has a universal flavor to it… but I’m no antelope hunter, and I don’t feel any blood relation to the mountain west which serves as his textured canvas.

Like McGuane, however, I have wanted to be a writer and a sportsman, to do what I do evocatively, and to find some value in the act of so becoming. Like him, I’ve wanted to collect my stories. This passage resonates as an example of how and why. It seems to me a metaphor for what Thomas McGuane, a writer and a sportsman, has mastered: the ability to isolate something moving quickly and at complex angles, suspending it long enough, and in clear enough terms, to examine closely. There are no mushy margins, there are no blurry edges. There is instead just fine-grained perception that unplaits the emotion, experience, and identity that twine in the human heart.

Thomas McGuane doesn’t see himself as a noticer. He told me so himself, walking over the hills, a worn-out Belgian Browning in one hand. He sees himself as a writer and a sportsman. But in the solitude of that identity, in the stories that describe it, there is nourishment, cohesion… some meaning to be made. For McGuane I’d guess, and for me too.

He follows the above passage with one of the finest points of punctuation I’ve yet to read:

“I stuck the knife in the ground and sat back against the slope, looking clear across to Convict Grade and the Crazy Mountains. I was blood from the elbows down and the antelope's eyes had skinned over. I thought, this is goddamned serious and you had better always remember that.”

First Published in Covey Rise