Among the Spruces

I saw my first spruce grouse when I was a hippy college kid, on a field study course that explored the ecology of James Bay, Quebec. Back then I had a more myopic view of the grouses, but one no less romantic. I’d been hunting ruffs through the corners of northern Vermont for a few years by then, attempting that drawn out northern inflection wherein they became p’atridge, and the softer r’s were omitted. These were our local birds, taken on the wing by the pipe-smoking few, and taken on the roadsides by the Labatt’s-drinking many, oft on the way to deer camp. I’m only somewhat ashamed to say that I took them both ways back then, and aspired to both typecasts, and still do in more ways than I often admit. The bird I saw slinking through the conifers in Quebec was altogether different, however, and has remained so in my memory, in and out of the decades since. It was a mottled hodgepodge of browns and chocolates and stark whites, feathered to the feet as the grouses are, and with a swatch of scarlet above the eye. I followed it noiselessly through the shadows for a near quarter hour, amazed that it would not flush. When it finally did, it merely hopped to a spruce limb at eye level and regarded me enquiringly. Clearly, the cockbird’s native intelligence told him that he’d nothing to fear from a hippy college kid… either that or I was the first human he’d seen, and he could make hide nor hair of this pale-faced interloper adrift in the landscape that had crafted him. Regardless, after a circumspect cluck, he sprung and bent through the brush, in a noteworthy tribute to his ruff-necked cousins south of the border.

Truth be told, I haven’t seen many spruce grouse since then. They are, by and large, a northern species, and though I’ve long haunted and hunted the northern fringes of our country, my sprucer sightings have been few and far between. There have always been stories of those friends who’ve shot one mistakenly, taking it for a ruff on the wing. These folks, several fine naturalists among them, tell a similar tale of surprise when the peeled breasts belie a rich purple flesh redolent of pitch and needles. I’d hunted them theoretically in an Alaska outpost, when days of sideways rain kept the fishing at bay, and the guides sent me out instead with a dog and a gun, that my fidgeting would no longer interrupt their drinking. “Down where the access road meets the tar, we’ve been seeing spruce grouse there,” they claimed, passing the bottle around the guide shack. “They’re in the little spruce stands by the road…” Guileless to a fault, I followed their direction, braving typhoon winds and sucking tundra and an access road that, no doubt to their delight, was a good five miles long. There were no birds, needless to say, but any walk with a gun and a dog fills the heart, and I went back on successive days with hope, if not spruce grouse, springing eternal. The guides got a kick out of that one.

In the early blush of middle age, I deigned to formally acquaint myself with Falcipennis canadensis, this time like a grown-up. I ventured north and west, into the heart of his native range, in the stronghold of one of a very few hunt-able regions in the lower 48. This happened to occur in a place I’d wanted to see since those same hippy college days, when I read Rick Bass’s tales of Montana’s shadows, and the spruce grouse that billowed from the hillsides of the Yaak.

The Yaak Valley is a low-lying chunk of northwest Montana. It is much like Vermont in both texture and tone, though the lilting speech is absent, the trees cast longer shadows, and there are wolf tracks in the sand. The one road into the Yaak describes a loop through next to nowhere. Believing in roads less traveled, I followed it, winding my way into a forest that traced the riverbed. A record fire year and untimely low water had done their meteorological dance through September, leaving the afternoon hazy with lingering smoke. What remained of the Yaak River winked through the pines, and I headed upstream into a day that hinted at premature evening. Deer and moose watched from the shoulder, considering ill-fated advances. Beyond the sparse center of Yaak, namely the mercantile, the Dirty Shame Tavern, and the one-room schoolhouse, the road jogged and crossed the river, looping eventually back south towards Libby. At the turn, a delta of spur roads and cart roads and elk trails and tributaries fanned north into perhaps the wildest country in the lower 48. At that spot, beneath a grove of pole aspens, I turned at the sign that read ‘Linehan’.

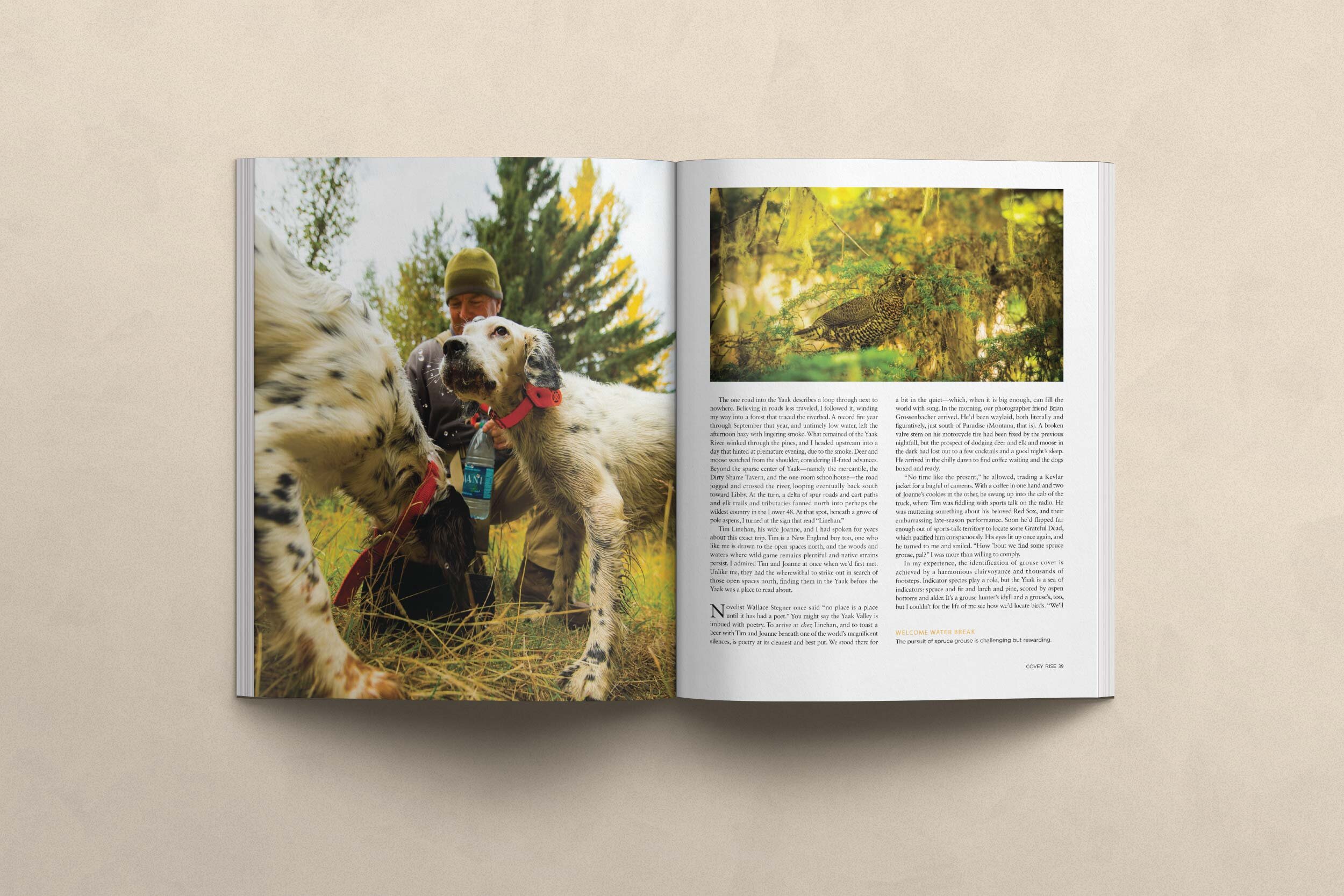

Tim Linehan, his wife Joanne, and I had spoken for years about just this trip. Tim is a New England boy too, one who, like me, is drawn to the open spaces north, and the woods and waters where game remains plenty and native strains persist. I admired Tim and Joanne at once when we’d first met. Unlike me, he and Joanne had the wherewithal to strike out in search of those open spaces north, finding them in the Yaak before the Yaak was a place to read about. Wallace Stegner once said that ‘no place is a place until it has had a poet’. You might say the Yaak has had its share. To arrive at Linehan’s, and to toast a beer with Tim and Joanne beneath one of the world’s magnificent silences, is poetry at its cleanest, and best put. By way of punctuation, Tim said “we’re really glad you made it, pal,” to which Joanne just smiled and nodded, fixing her bare feet firmly on the cold ground. I felt, in the face of all that, as though I couldn’t agree more. We stood there for a bit in the quiet, which, when it is big enough, can fill the world with song.

In the morning, our photographer friend Brian Grossenbacher arrived. He’d been waylaid, both literally and figuratively, just south of Paradise (MT). A broken valve stem on his motorcycle tire had been fixed by the previous nightfall, but the prospect of dodging deer and elk and moose in the dark had lost out to a few cocktails and a good night’s sleep. He arrived in the chilly dawn to find coffee waiting and the dogs boxed and ready. “No time like the present,” he allowed, trading a Kevlar jacket for a bag full of cameras. With a coffee in one hand and two of Joanne’s cookies in the other, he swung up into the cab of the truck, where Tim was fiddling with sports talk on the radio. He was muttering something about his beloved Red Sox, and their embarrassing late season performance. Soon he’d flipped far enough out of sports-talk territory to locate some Grateful Dead, which pacified him conspicuously. His eyes lit up once again, and he turned to me and smiled. “How ‘bout we find some spruce grouse, pal?” I was more than willing to comply.

In my experience, the identification of grouse cover is achieved by a harmonious clairvoyance and ten-thousand footsteps. Indicator species play a role, but the Yaak is a sea of indicators: spruce and fir and larch and pine, scored by aspen bottoms and alder. It’s a grouse hunter’s idyll and a grouse’s too, but I couldn’t for the life of me see how we’d locate birds. “We’ll find ‘em, pal,” assured Tim. “We always do.” And of course I should have trusted him; as the gravel road bent south up a hillside, two indistinct lumps appeared on the shoulder. Tim crept the truck up slowly for a better look. I rolled down my window, and Grossenbacher did too. The two birds were young of the year, pecking grit, barely noticing the rumble of the idling truck. We watched them till they turned, and bobbed back into the forest. Tim put the truck back in gear, and continued up the hill, smiling and whistling with Bobby’s rhythm and Jerry’s lead.

Northwestern Montana is a webwork of cart roads and logging traces, some long overgrown. We stopped at the end of a nondescript one and got out, kicking the previous day’s travel out of our joints while Tim kissed and collared the dogs. Tim’s eyes sparkle most when he’s with his dogs, and as if in giving into schoolroom indiscretion, a twinge of a Boston accent returns when he addresses them. The young setter, Maggie, gets the worst of it, losing nominal consonants and a wee bit of dignity when her doting father refers to her lovingly as “Maahhgret”. But parental humiliation is a pain worth suffering when the beepers touch off and the bell goes on Gracie, the olden Golden. Maisey, the elder setter, is already off on a tour of the roadside, snaffling and feigning birdiness. I’ve seen enough to load my gun and be ready. The puppy follows suit, spinning through the pucker brush and coming up short to relieve herself in a steaming pile, beside where a wolf last night did the same. “Hey Reid, she’s pointing at you,” announces Grossenbacher, relishing the joke that he favors for me, and eliciting a giggle from Tim. But by then the pup, much enlightened, heads off to hunt in earnest, and the old dogs are already gone. The bells and beepers grow abstract, and the heavy silence of the Yaak descends, blanketing the world in stillness once more. We snick our guns closed and plunge into the forest, into traces of trickling sunlight.

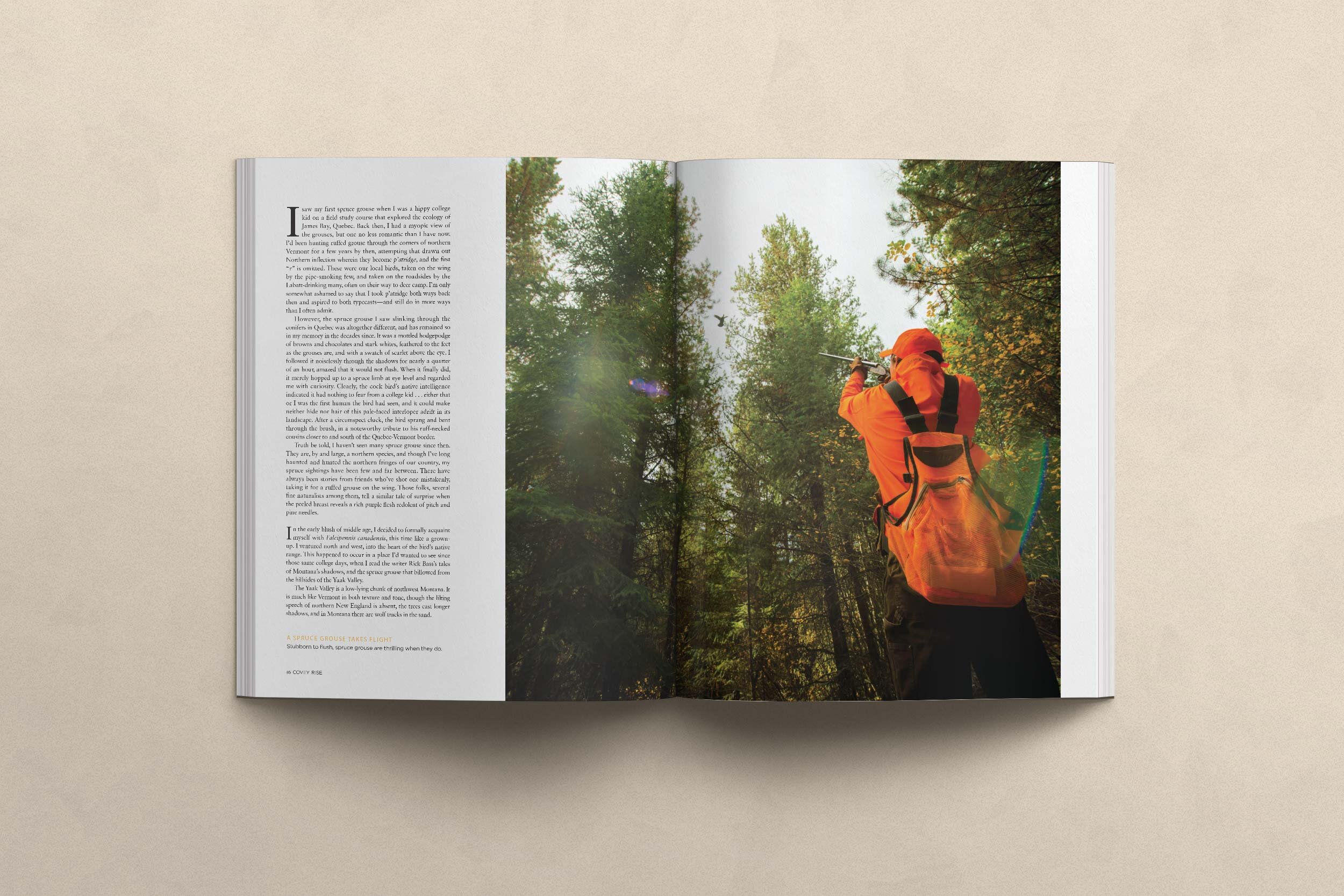

In the Yaak, you’d be hard pressed to not see the forest for the trees. Each one is magnificent, and where the mature forest rises and chokes out the understory, it becomes a cathedral. The silences and shadows are churchlike, the colors simultaneously muted and brilliant. Only when something familiar as a bird dog lopes infront of one does the scale of the place descend. Tim looks out through a break towards the faraway ridgeline, where the larches are turning one by one, going gold from the top down, dabbing the hill in color. “Like so many burning candles…” he says, as if to nobody, and again the Yaak is alight with poetry. Far up the cart road a beeper sounds, steady rhythmic. Tim stops and cocks his head, and then smiles, turning as he does so. “Got a point, pal!” We both open guns and begin to run. Well up the side hill the beeper continues, and Gracie loops back around for a bit of the action. The sound continues up above us, and there is no white setter to be seen. We follow the sound, leaning into the hill and scrambling up, slipping back routinely, stopping to breathe hard, wondering if we should just let this point go. “Take your time,” we tell each other, as much for the respite of a few words. The beeper continues, and there against the hill is a high-tail dog bending over a big dead spruce, intent on the brush. A young white setter is ranging into sight, and above us further a Golden gets to barking, making Tim smile and lean against a tree. “Get up on that point, quick… that bird is gonna bust!” With a heart beating exertion and hope, and a twenty-year daydream unraveling beneath my feet, I take another step and close the gun. A quivering dog breaks free and a wedge of ground does the same, and a mottled blur pursues the contour of the hill between the spruces. I fire once, mechanically seeing the impacted flight change course, and I fire again to be sure. With a momentum that carries it forward, pushed more so by the shock, the bird tumbles down with a softened thump that, despite the barking Gracie and the echoing shot, the Yaak amplifies with a surrounding silence. Time is suspended, if just for a moment.

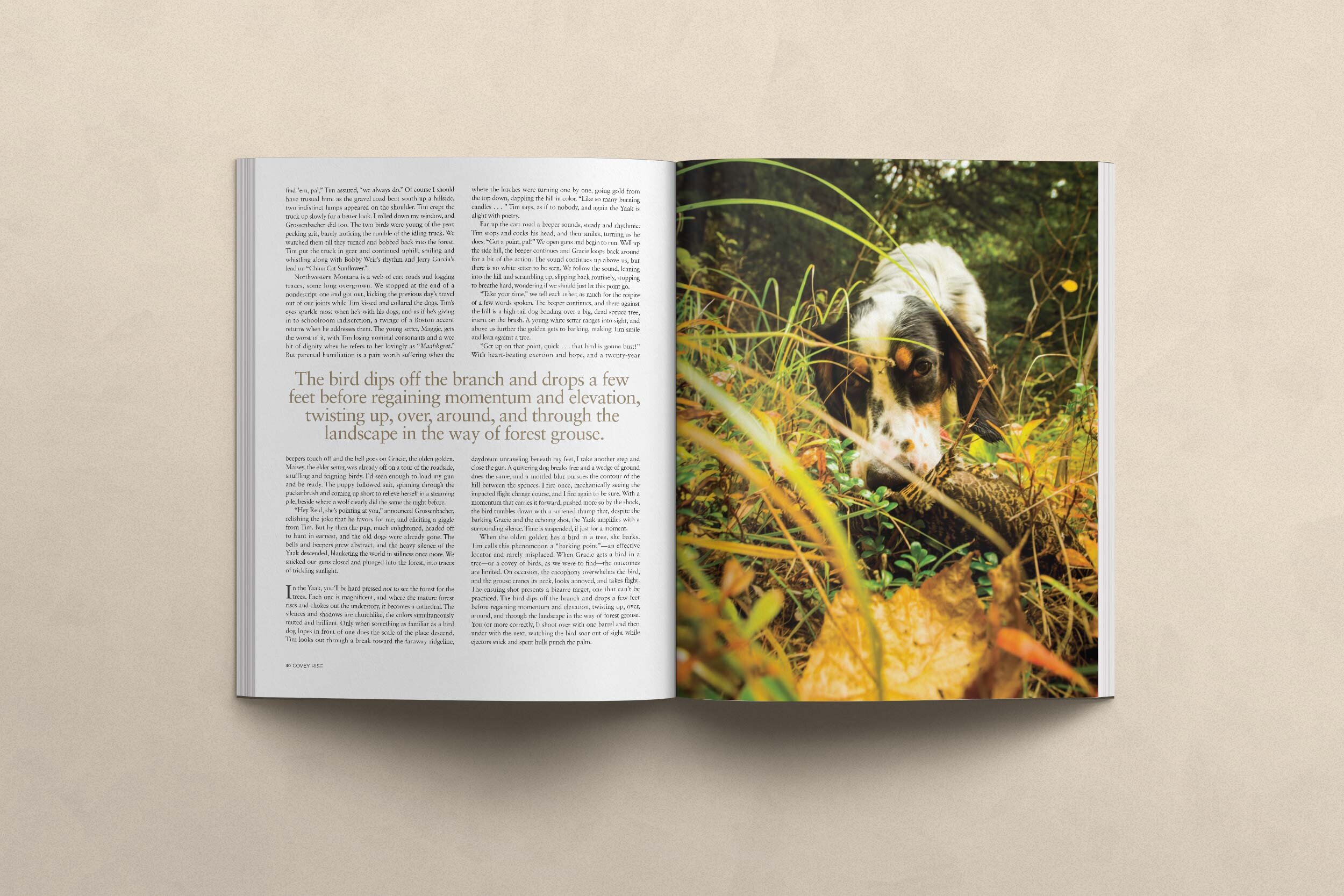

When an olden Golden has a bird in a tree, she barks. Tim calls this phenomenon a “Barking Point”; an effective locator and rarely misplaced. When Gracie gets a bird in a tree, or a covey of birds as we were to find, the outcomes are limited. On occasion, the cacophony overwhelms the smaller party, and the grouse cranes its neck, looks annoyed, and takes flight. The ensuing shots present as bizarrely as any, and can’t be practiced for. The bird dips off the branch and drops a few feet before regaining momentum and elevation, twisting up, over, around, and through the landscape in the way of forest grouse. You, or more correctly, I, shoot over with one barrel then under with the next, watching the bird out of sight while ejectors snick and spent hulls punch the palm. In the leaner days of a grouse hunter’s calendar, a crack at a roosted bird is sorely tempting. The Labatt drinker in me contemplates ethics, but of course the roosted birds are too proud for the easy pickings. In light of these thoughts and more, the barking of a Gracie dog becomes too much for the hunters, who have a first sprucer on the ground after all, and would appreciate the reverie of a bark-less moment. Tim calls Gracie off the young and the roosted, and sends her on the retrieve, which she performs admirably. The pup turns circles around her with a helicopter tale, though stately Maisey has moved off in search of things more in reach of her finely-tuned nose. As is my wont, I take that bird from Tim, who’s taken it from Gracie, who is now receiving her anticipated praise and a pull from the water bottle.

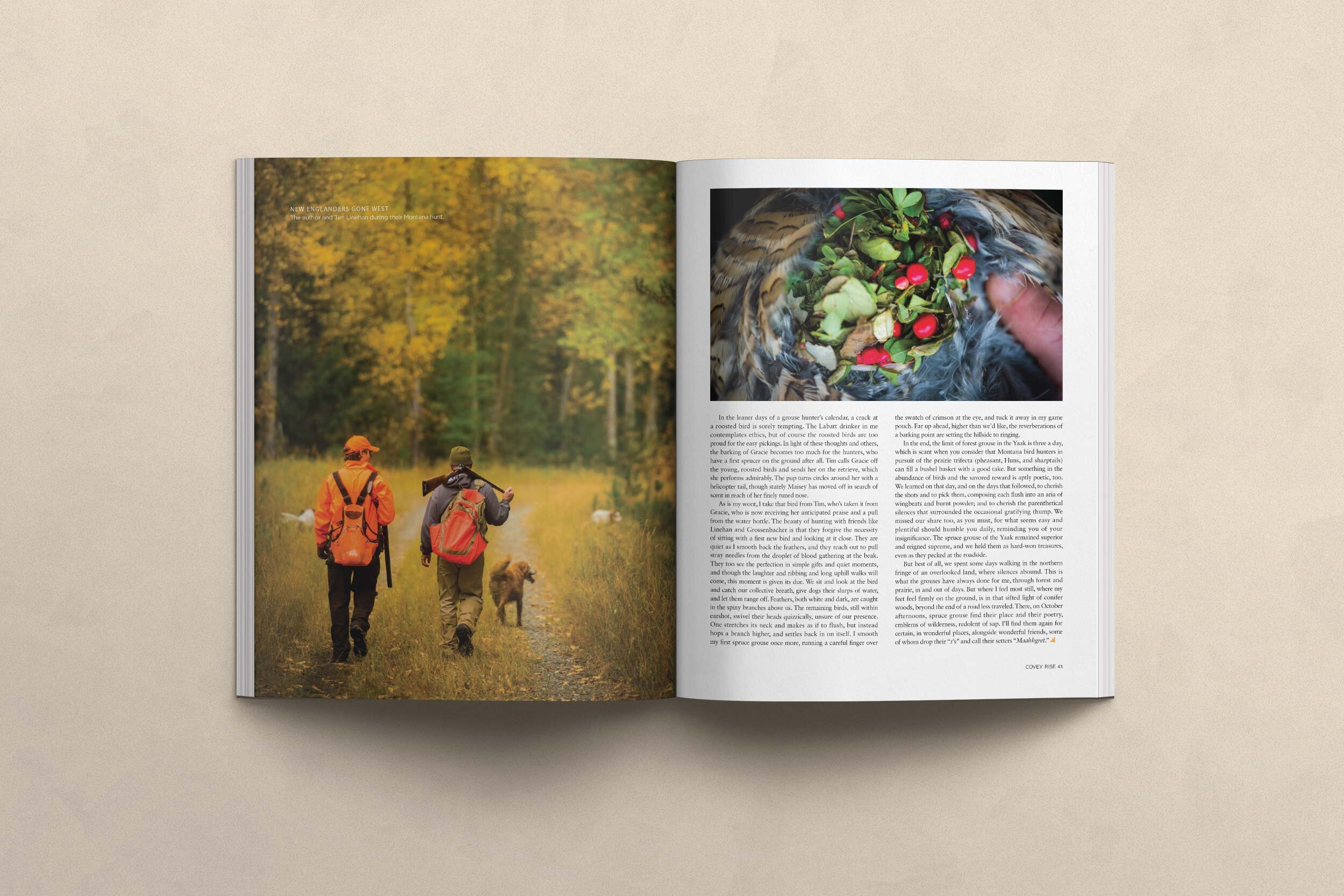

The beauty of hunting with friends like Linehan and Grossenbacher is that they forgive the necessity of sitting with a first new bird and looking at it close. They are quiet when you smooth the back feathers, and they reach out to pull stray needles from the droplet of blood gathering at the beak. They too see the perfection in simple gifts and quiet moments, and though the laughter and ribbing and long uphill walks will come, this moment is given its due. So we sit and look at the bird and catch our collective breath, give dogs their slurps of water, and let them range off. Feathers, both white and dark, are caught in the spiny branches above us. The remaining birds, still within earshot, swivel their heads quizzically, unsure of our presence. One stretches its neck and makes as if to flush, but instead hops a branch higher, and settles back in on himself. I smooth my first spruce grouse once more, running a careful finger over the swatch of crimson at the eye, and tuck it away. Far up ahead, higher than we’d like, the reverberations of a barking point are setting the hillside to ringing.

In the end, the limit of forest grouse in the Yaak is three-a-day, which is scant when you consider that Montana bird hunters, in pursuit of the prairie trifecta (pheasants, huns, and sharptails) can fill a bushel basket with a good take. But something in the abundance of birds and the savored reward is aptly poetic too. We learned in that day and the ones that followed to cherish the shots and to pick them, composing each flush into an aria of wing beats and burnt powder, and parenthetical silences that surrounded the occasional gratifying thump. We missed our share too, as you must, for what seems easy and plentiful should humble you daily, reminding you of your insignificance.

The spruce grouse of the Yaak remained superior and reigned supreme, and we held them as hard-won treasures, even as they pecked at the roadside, innocent of our misbegotten intentions. But best of all, we spent some days walking in the northern fringe of an overlooked land, where silences abound. This is what the grouses have always done for me, through forest and prairie, in and out of days. But where I feel most still, where my feet feel firmly on the ground, is in that sifted light of a conifer woods, beyond the end of a road less-traveled. There too, on October afternoons, spruce grouse find their place and their poetry, emblems of wilderness, redolent of sap. I’ll find them there again for certain, in wonderful places, alongside wonderful friends, some of whom forget their r’s, and call their setters “Maahhgret”.

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine