The Choices We Make

Better than half a lifetime of shooting at birds has taught me this, if nothing else: hunting is an imperfect act, assumed by imperfect people. Over the years, I’ve wandered around with a gun and a dog and a sense of intention and a bit of luck, and I’ve knocked down my share and been gratified to do so. Equally equipped, I’ve also raised my gun and pulled the trigger only to miss, or to assume I’ve missed, as many times as the next guy. I suppose that hunting wouldn’t be hunting, and my connection to it would not remain strong, were my intentions always realized. For better or worse, it’s unrealized intentions that have informed in me the complex responsibility that comes with being a hunter. Whether my shots land or not, I’ve learned they have an impact.

Some years ago, on South Dakota’s Rosebud Reservation, I spent a few days looking for sharp-tails on ground that was made for them, and them for it. My friend Steve was running a string of setters that had been finding birds with precision and style, and we’d shot a good number of them. As a system comprised of dogs and men, we’d assumed that easy confidence that precedes success, and though I’m sure we missed a few, I’m also sure it wasn’t many. Which is why, when a pinned single got up at my 2 o’clock and crossed my bow going left, I mounted the gun and pulled both triggers, already counting another bird towards my limit. I saw the bird fold and fall just beyond a two track, so I continued walking through the original point as sharp-tail hunters should, hopeful for a lay bird or more. When the dog broke and kept on hunting, I swung back to pick up what I’d dropped, and Steve watched me, indicating that he had a good mark. I knew I wouldn’t need his steering. I walked over to where the bird had fallen in some cropped grass, certain it would be laying there, a piece of meat both lifeless and plain as day.

It wasn’t.

I dropped my hat and started doing circles. The ground was nearly bare, only a few inches of grass and a hint of a road and more of the same throughout the widening concentric rings I traced, but there was no bird. Not a cut feather. Not a drop of blood. And though we called the dogs back in and had them hunt dead in the area for what seemed an eternity, that bird had simply vanished. We gave the search its due, and we reconstructed the scene and all its possible permutations, but we eventually called it a loss.

It didn’t feel good, but hunting wasn’t designed to feel good all the time. At points it simply doesn’t go as planned, and we still had a day and many miles to go, so we turned our attention away from what we’d lost and towards what was yet undetermined, and we kept on hunting. I remember tidying up the loose strands of my conscience with the consolation that the bird was hard hit, would likely perish quickly, and would in turn become the easy meal of whatever in that ecosystem gobbled up the unrealized intentions of guys like me. If I’m honest, I began to feel almost ok about this inadvertent act of charity.

My conscience had other designs, as you can see, and I’ve never forgotten that bird. One disappearing sharp-tail has become a recurring character in the honest dialog I increasingly hold with myself about the harm I do, and the misalignment of my intentions and my actions. What was for a moment a tidy equation wherein I lost a bird, another animal got an easy meal, and all was right with the world, has come to include more variables and more unknowns. Among them, I’ve begun to think that the dose of lead shot I used to suspend that bird became an unintended ingredient in the equally unintended meal I delivered to a delicate ecosystem, and whatever came along and ate that grouse was, unlike me, incapable of separating the less desirable bits from the whole. As I said before, hunting is imperfect, and so am I; the complexity of that imperfection leaves more questions than answers, and I’m starting to think that I should see each shot fired as the first in a long line of dominoes, many of which I’ll never stick around to see topple into the next.

***

Amed with little more than unanswered questions, I huddled with a team of avian biologists on a high ridge in central Montana, not far from the Continental Divide. This ridge runs roughly north-south, and a few miles off, a similar ridge runs nearly parallel. Each autumn, birds of prey follow the valley between these ridges on their migratory path, some traveling from the Arctic all the way to Mexico. Golden Eagles, Bald Eagles, Sharp-shinned Hawks, Coopers Hawks, Kestrels, and a parade of other species ride the favorable updrafts south, watching the great American landscape unfurl beneath them. Also each Autumn, the team I’d joined settles into a small box blind perched on the slope of that southern ridge to watch. Their goal is to monitor the passage and to keep record of bird count, and to trap what birds they can for more categorical analysis. To bring the birds to hand, the researchers play into the raptors’ prey drive, using live decoys to tempt the birds from miles off into a small bench of flat ground a few yards from the blind. As the raptors land to seize their prey, one of the scientists deftly tugs a string fastened to the trigger of a spring-loaded net. And when all goes to plan, the net releases, hinging like a clamshell to close over the bird.

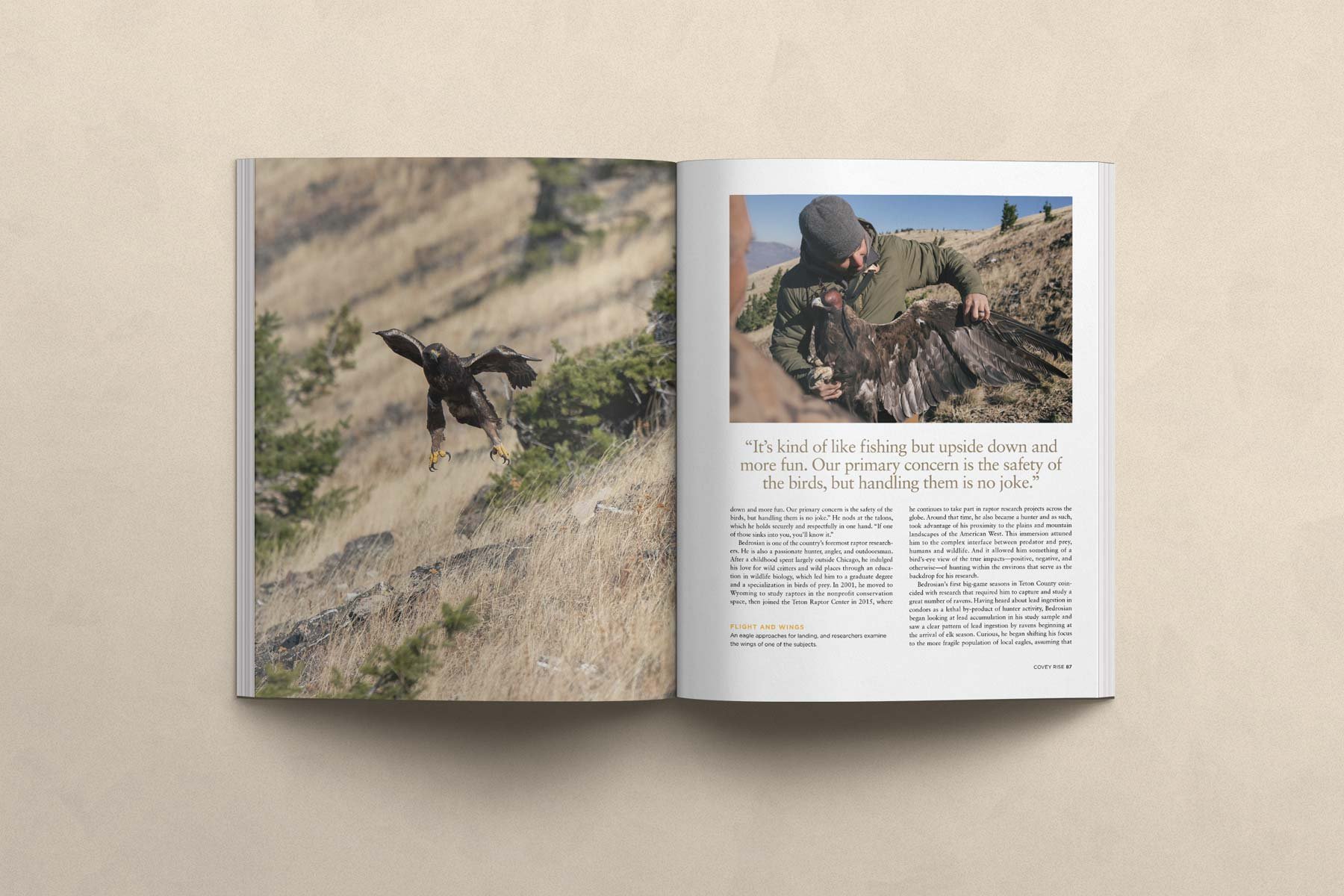

A whirlwind of activity ensues. The researchers race out of the blind, grasp the bird and extract it from the net, cover its head with a leather hood, and swaddle it in a cloth jacket that renders its wings incapable of motion. Though the bird is effectively immobilized and unable to see at this point, the researchers remain keenly aware of the talons which, in the case of the Golden Eagle, can clamp down with a grasping strength that human hands are physically incapable of releasing. Says lead researcher Bryan Bedrosian, “it’s kind of like fishing, but upside down, and more fun. Our primary concern is the safety of the birds but handling them is no joke.” He nods at the talons which he holds securely, and respectfully, in one hand. “If one of those sinks into you, you’ll know it.”

Bedrosian is one of the country’s foremost raptor researchers. He is also a passionate hunter, angler, and outdoorsman. After a childhood spent largely outside Chicago, he indulged his love for wild critters and wild places through an education in Wildlife Biology, one that led him to a graduate degree and a specialization in birds of prey. In 2001 he moved to Wyoming to study raptors in the non-profit conservation space, then accepted a position with the Teton Raptor Center in 2015, wherein he continues to take part in raptor research projects across the globe. At about the same time, he became a hunter, and as such took advantage of his proximity to the plains and mountain landscapes of the American West. If anything, this immersion attuned him to the complex interface between predator and prey, humans and wildlife, and allowed him something of a bird’s-eye view of the true impacts, positive, negative and otherwise, of hunting within the environs that served as the backdrop for his research.

Bedrosian’s first big game seasons in Teton County coincided with a period of research that required him to capture and study a great number of ravens. Having heard about lead ingestion in Condors as a lethal byproduct of hunter activity, Bedrosian began looking at lead accumulation in his study sample and saw a clear pattern of lead ingestion by ravens beginning at the arrival of elk season. Curious, he began shifting focus to the more fragile population of local eagles, assuming that scavenging behaviors similar to those of ravens would elicit similarly elevated lead levels. Bedrosian’s suspicions were well founded, and his research proved the point: with the arrival of hunting season, the eagles of Teton County showed a marked increase in blood lead levels. Bedrosian tracked several of these birds through the course of the season only to find them sick, dying, or dead. He retrieved these birds for rehabilitation and/or forensic analysis, and certified that the impetus for the episodic debility of local eagles was lead toxicity.

A Golden Eagle, like many birds of prey, exists exclusively on a diet of meat comprised of living prey and carrion. Once that meat is attained, it is initially ingested into the crop, which serves as a storage vessel in the gullet, one that allows the bird to accumulate as much feed as possible when opportunity arises. Next, the Eagle locates a safe perch, at which time the meat moves from the crop to the proventriculus, or first “true stomach”, where highly acidic chemical digestion dissolves the bulk of fur, feather, bone and flesh. Finally, what remains of the meal passes into the gizzard, where the slurry is ground mechanically, and whatever proves undigestible is concentrated into a pellet for regurgitation. As Bryan pursued the toxicity pathway in Eagles, he surmised that the problem was ingested lead which, during the latter two stages of digestion, made it into the bloodstream to negatively impact a host of the Eagle’s biological systems. Presentations of lethargy, ataxia (impaired coordination), weight loss, muscle weakness, respiratory depression, and seizure were rendering these iconic birds incapable of hunting and scavenging, and, barring intervention, were causing fatalities that were both too frequent, and apparently connected to hunter activity.

As Bedrosian continued to follow the breadcrumb trail to its source, he found that the gut piles left by big game hunters often contained lead fragments, big and small. Ballistic testing went on to confirm that upon impact, a lead projectile mushrooms as designed, with the overlooked consequence of sending tiny particles erratically beyond the point of impact. Hence, when the gut pile was left in the field for the scavengers to clean up (an age-old and presumably harmless practice), an incidental volume of lead was being ingested by scavenging Eagles and other carrion eaters. Using similar reasoning, Bedrosian found that crippled gamebirds that were hit with lead shot and unrecovered were presenting a like pathway for lead ingestion in avian and other scavengers, particularly in areas of high-concentration bird shooting throughout the west. The uptick in sick Eagles during hunting season was sound anecdotal proof of Bedrosian’s hypothesis, but scientific rigor required a bit more research. With that, Bedrosian took it upon himself to pass out lead-free big game ammunition during a few of the following seasons to compare blood lead levels in those birds studied during previous seasons in Teton County. The results were incontrovertible: even with only partial adoption of lead-free ammunition, lead accumulation and toxicity saw a statistical decline, and fewer raptors were suffering at the hands of hunters.

The challenge of a scientific finding in many cases is the recognition of a problem followed by a recognition of the many roadblocks that rise up to impede the path towards a solution. In the case of lead and Eagles, Bedrosian had landed on a solve that was both simple and immediate. Were hunters to make the informed decision to pivot to lead-free ammunition alternatives, fewer Eagles would suffer. This equation proved quite beautiful in its simplicity, and empowering in that each individual adoptee was given the chance to make a felt impact. The challenge then was education, communication, and adoption.

This latter need led Bedrosian to form Sporting Lead-Free in 2021. As an organization, SLF attempts to “increase awareness and education so that hunters can make informed decisions and avoid the top-down, regulatory approach. Our focus is to promote education, not legislation.” The thinking behind this mission is unique, as noted by the org’s intentional lack of focus on legislation. “I think about it this way,” says Bedrosian. “I don’t want anyone to tell me what to do, and I don’t want to tell anyone else what to do. But I also want to make informed decisions. I want to ensure that I know the downstream impacts of my actions. I want to hunt and fish and eat game, and I also want to make sure that I am doing all I can to protect the ecosystems and species that I love. Moreover, I want to make sure that I do what I can to avoid being constrained by legislative action. If, as a hunter and a citizen, I can make choices that protect vulnerable species and delicate ecosystems, then I don’t have to worry that degradation of those species and ecosystems will give rise to more laws, or mandated restrictions. I want to preserve the heritage, and I want to preserve the resources that allow me free access to that heritage.”

He goes on: “From an education standpoint, I also want people to know about the real impacts of lead toxicity, not just on wildlife, but on human health. In general, incidental lead ingestion by adults, either via bird shot or lead fragments in game meat, is relatively low-risk. Ingestion by children or pregnant women is another story. In Teton County, we have X-rayed nearly 7000 pounds of game meat, both that retained by hunters and donated. Close to 20% of that meat contains lead fragments. I for one don’t want my children, or anyone else’s children, eating that meat.”

It's sound counsel. The dominoes topple in a long and circuitous train, one that includes the health of both land and people, species and the ecosystems that either promote their health or threaten it. And sometimes that first domino to fall contains some incidental lead, though it doesn’t have to.

***

As I sat on the side of a mountain fishing for Eagles with Bryan Bedrosian, there was a great deal of time spent just watching, looking out over an epic piece of windswept America that felt utterly unbounded, and absolutely wild. Far, far down the valley, many miles away, we’d periodically catch sight of something floating, slipping closer almost atomically, and taking on definition. Eventually it would become a shape, a splinter of black against mountain and sky, rising and falling almost imperceptibly. It seemed impossible when, from miles out, the wedge would change course and sideslip a bit closer to our ridge. Eventually, through binoculars, I’d make out a head pivoting, keying in on our location, and the bait we were presenting. And then, with speed and conviction that I still struggle to comprehend, it would swoop upon us, talons extended, wholly given to its predatory call. The ensuing testing, the collection of body metrics and blood samples, the requisite leg banding, was fascinating for its intimacy, but something about those huge birds bound and restrained impressed a sense of compromise that none of us really enjoyed. I suppose that is why the scientists worked swiftly and efficiently, gathering their data for later study of lead levels and other toxins, and then hustling back up the hill to release each bird to its purpose. Unhooded, unbound, and held carefully by breast and talons, the birds would barely struggle. But the ferocity in their eyes blazed with a fire that humans can neither muster nor fully comprehend. Then, with a loosening of the researcher’s grasp, the birds would go upon their journey, rising on the thermals, aware again of a landscape over which they seemed to have ultimate reign, despite the brief indignity. They’d disappear almost immediately.

By design, a blind on the side of a mountain is a place for consideration. Sitting in this one in Central Montana, I thought a great deal about myself as a hunter, and the intentions I bring with me, along with the dog and the gun. I thought about my fallibility, and the harm I do, and the impact I have. I thought about a grouse I couldn’t find in close-cropped prairie grass, knowing that it was there somewhere, part of a process I’d set in motion. I thought of all the other creatures I’ve no doubt crippled and lost, and all the gut piles I’ve given back to the landscape.

I also thought about Bryan Bedrosian, his awareness that as hunters we will be imperfect, but as conservationists we have a great deal of agency. Bryan refuses to feel powerless. His power is reflected in a firm command of his ability to protect what he loves, and to invite others to do the same. Bedrosian is emphatic on this point. “Again, I don’t believe in telling people what to do. But I do believe that given all the information, and given choice, people can make informed decisions for themselves. There are few examples of liberty as iconic as the Eagle, and I can tell you that the sight of an Eagle dying slowly from lead poisoning does something to a person. I think that most of the hunters I know would choose to prevent such a death if they knew they could.”

First Published in Covey Rise Magazine